Atlas of Forensic Culture – The Netherlands

By Lara Bergers

In some ways, murder cases, which have served to provide much of the source material for historians interested in forensics, are not the best cases to learn about a forensic culture, because they typically form a very small minority of the crimes that are investigated by police and judicial actors. Their exceptional nature can sometimes distort the understanding of a forensic culture; the 1952 case narrated below, for example, stands out from lesser contemporaneous crimes in the Netherlands -even ones as serious as rape – by its heavy reliance on several forms of forensic expertise. It also stands out because of the fairly extensive verbal statements by several investigators and experts at trial; Dutch forensic culture has been very reliant on written reports.

Of course, it is precisely these exceptional characteristics that make this case – and murder cases more broadly – useful for understanding how forensic science was employed when it did play an important role. This case shows how forensic expertise served to legitimize conclusions that were also drawn by non-specialist participants in the investigation. In the autumn of 1950, Hendrik (pseudonym), a farmer who ran a small farm with his aging father Aart (pseudonym) and aunt Cornelia (pseudonym,) placed a marriage advertisement in the local newspaper. He hoped to find a nice wife, who might help support his business as the work became too hard for his father and aunt. The 38-year-old Mien (pseudonym) from a nearby village responded to the ad and after a short courtship, in December op 1950, Mien and Hendrik married. Seven months later, however, on a Sunday morning in July of 1951, having just returned home after milking the cows with his father, Hendrik ran to get his neighbour, indicating something terrible had happened. When the pair made their way to the attic they were confronted by Mien’s body, hanged by the neck from a ceiling beam. Together they cut her down. The neighbour’s wife, who had come up after hearing the commotion, went to fetch the local doctor and police officer. When they arrived on the scene, the doctor declared Mien dead and the police officer began an investigation into the circumstances of her demise.

If on first sight the case had appeared a suicide, such an impression did not last long. The first officer on the scene, Van Breugel, noted not only that Hendrik’s behaviour was somewhat strange, but also that there was blood on Mien’s face and throat. When Van Breugel interviewed Hendrik and Aart, they declared that she must have hanged herself while they were out to milk the cows – but Van Breugel and the local doctor observed that rigor mortis had already set in. Thus, foul play became the leading hypothesis almost immediately. Van Breugel made sure that no one touched the crime scene while they waited for higher ups and the experts to arrive.

The first on the scene was F.A. Mulders, a photography expert tied to the national police. From the time that it became commonly embedded in police practice, photographic expertise was connected to other types of forensic expertise, including fingerprinting. The photos, which are preserved in the case file, show clearly that Mulder knew where to look; in addition to a couple of overview photos, he took photos of the victim, especially of the marks on her neck and he took a photo of the cut rope that remained attached to the ceiling beam. Most importantly, however, Mulder seems to have immediately realized that the bed on the side of the room was a crime scene. He took a photo of the sheets, which had a stain on them, and of the foot of the bed, where two boards were broken. In his report he clarified that the stain was wet – also noting that the floor under the place where Mien had hung was dry. He also noted that the state of the bed had made him suspect that a struggle took place there.

The casefile shows that pathologist Jan Zeldenrust made it to the crime scene on the same day. Although Zeldenrust’s main task was to perform the autopsy and write a report for the court, he also observed the crime scene. In his report, he noted the same things that Mulder had observed, but where Mulder had only reported the sight of the yellow-brownish stain on the sheets and the victim’s underwear, Zeldenrust noted that those stains smelled of urine.

Mien’s body was moved to the local hospital, where Zeldenrust performed the autopsy in the hospital’s chapel. As was always the case, the post-mortem report took the shape of a numbered list, that went over every external and internal part of the body, describing any and all irregularities, that could have contributed to the death. Zeldenrust concluded that Mien’s death was the result of strangulation and that she had already been dead when her body was hung from the ceiling beam, confirming the suspicion of seemingly everyone who had participated in the investigation thus far.

In addition to the crime scene investigation, several pieces of physical evidence were transported (in a Hessian bag) to the newly established forensic laboratory in Den Haag. The director of the new institute, Wiebo Froentjes, investigated blood traces on a chord that was found later and which seemed to have been employed in the efforts to strangle the victim, while chemist Anton Hendrik Witte extracted the victims clothes and the confiscated sheets to demonstrate the presence of ureum: indeed, the stains were urine.

Of course, the investigation revolved around more than just the physical traces: interrogations of the members of the household showed a strained relationship between Mien and her new family; they found her to be lazy and difficult and their catholic sensibilities were offended by her sunbathing. Neighbours and Mien’s siblings confirmed the strained relationship, saying Hendrik, Aart and especially aunt Cornelia were controlling and unkind. it would not be long before both Hendrik and his father Aart confessed that they were involved in killing Mien, although the two men were inconsistent about the details.

A notary came forward to tell the police that Hendrik had visited him asking about divorce, but he – as a devout Catholic himself – had told his visitor to try his best to work it out. Both the investigative judge and the psychiatrist who examined the two suspects later asked about this: why not file for divorce if the marriage was so unhappy? Surely, the shame of divorce would not have been as bad as the shame of murder? Hendrik answered that they did not think anyone would find out. The psychiatrist actually made much of the family’s ‘backwards’ Catholic sensibilities, arguing that the perpetrators could only be held partially responsible on the basis of it.

At trial, several police officers testified to what they had seen and Zeldenrust, too, was present to answer questions. Froentjes and Witte, working at the same location in Den Haag, had entrusted the physical evidence to Zeldenrust, who delivered it to the court. Upon seeing all the evidence, the court convicted Hendrik to twenty years in prison, which was later modified to seventeen by the court of appeals, and Aart was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. The court remarked that the crime was particularly heinous, because the victim was the offenders’ wife and daughter in law.

1886

New Criminal Law

The new criminal law comes into effect. A partial insanity defense is not yet applicable in the parameters of this law. The use of medical expertise is dependent on the presiding judge

1911

Introduction of article 248bis

New laws governing sex crimes come into effect, including the institution of infamous article 248bis.

Dina Sanson

The first female police officer, Dina Sanson, starts working with the new department for youth and sex crimes in Rotterdam.

1914

First school for Criminalistics is opened in the Netherlands by Co van Ledden Hulsebosch

1916

Van Ledden Hulsebosch becomes scientific advisor

Van Ledden Hulsebosch becomes the scientific advisor at the investigative team of the Amsterdam police. Later on, he would also serve in the same position in Rotterdam

1926

New Criminal Procedure Code

A new Criminal Procedure Code comes into effect. Statements made in legal procedures by an expert and the report of the expert are now accepted as evidence.

1928

Psychopath Laws

The “Psychopath laws” come into effect. Partial insanity and the ‘TBR’ (Provision to the Government) are instituted.

1929

Van Ledden Hulsebosch co-founder and first chair of the Académie internationele de criminalistique

1930

The book "First Actions at the Scene of the Crime" by Willem Schreuder is published

1933

Establishment of the Leiden Criminological Institute

Source: Website of the NFI

1946

The book "Wetenschappelijk opsporingsonderzoek" by Willem Schreuder is published.

Judicial Physics Laboratory

The Judicial Physics Laboratory is established in The Hague, led by dr. Wiebo Froentjes.

1949

Establishment of the Clinic for Psychiatric Observation

1950

Psychologists can be consulted

From the 1950s onwards, as well as psychiatrists, psychologists can now also be consulted in criminal investigation procedures and/or legal procedures.

1951

Judicial Medical Laboratory

Opening of the Judicial Medical Laboratory in The Hague. The pathologist, dr. Zeldenrust, worked at the Judicial Physics Laboratory between 1947 and 1951, and the institutions remained closely connected afterwards.

1960

Judicial Laboratory becomes too small

The Judicial Laboratory becomes too small due to technological changes, such as the development of instrument-based analysis and modern electronics.

1973

Bigger location for the Judicial Laboratory

The Judicial Laboratory moves to a bigger building and starts working with the Forensic Investigative Services (Technische Opsporingsdienst)

1984

Dr. Zedenrust retires

Below is a short discussion of the general characteristics of the Netherlands and the context in which its forensic culture developed.

The Netherlands is a parliamentary representative democracy and a constitutional monarchy. The country is made up of twelve provinces – eleven until the establishment of Flevoland in 1986 – which sit between the national and local level of government (the gemeentes.) Between the May 10th, 1940 and May 4th, 1945 the country was occupied by Germany.

From the late 19th century, Dutch society was pillarised along religious and political lines. This social and political reality, which saw members of different groups living, to an extent, parallel lives, with different political parties, schools, press and professional organisations, began to change in the 1960s.

The Netherlands was the colonial ruler of Indonesia, which declared itself a republic after the Second World War. The Netherlands accepted its former colony’s independence in 1949 and relinquished control over Western New Guinea (now Papua) in 1963. Former colonies Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles (then known as Curaçao and dependencies) became constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1954. Suriname became independent in 1975.The Dutch Antilles were dissolved in 2010.

The Netherlands was a predominantly Christian country during the twentieth century. The proportion of Protestants and Catholics within that majority shifted over time, as secularisation proceeded faster for protestants than it did for Catholics. The small Jewish community was all but destroyed during the Second World War. Since the 1970s the Netherlands has been home to a small but growing Muslim community.

Between the late 19th century and the late-1960s, the country was pillarised along religious and political lines.

The Dutch legal system consists of three areas; civil or private law, administrative law and criminal law. The following pertains only to the latter.

The Dutch legal system can be characterised as inquisitorial, although the use of this term is not entirely uncontroversial. Fact is, however, that criminal investigations are formally led by an investigative judge. Witness reports, expert reports, police reports and any other evidence that is collected during the investigation is collected in the case file, which is handed over in its entirety to the trial judge or judges. Any expert witnesses involved in the case are appointed by the investigative judge or the trial judge(s), though the defence can request counter expertise. The right to counter expertise was expanded significantly after the introduction of DNA evidence. The Dutch legal system knows no jury.

If a case is appealed, an appeals court (Gerechtshof) will reconsider the evidence in the case in its entirety. If a case is appealed to the supreme court Hoge Raad, that court, if it chooses to hear the case, will consider the legal arguments at play.

The currently active criminal code (Wetboek van Strafrecht) has been in force since 1886, when it replaced the French Code Pénal. The code of criminal procedure (Wetboek van Strafvordering) dates from 1926; the process to replace the code is currently underway.

In the first half of the 20th century, the male breadwinner model of the family was the norm. Emphasis was on the duty of men to provide for their family, and the duty of women to create a home that was a haven in which children could grow up safely. Around the turn of the century, the state showed itself willing to intervene if the home environment proved lacking. The 1905 children’s law gave judges the power to remove children from parental authority in cases of neglect or maltreatment, created a separate juvenile criminal law system and set down rules for institutes for re-education.

The children’s laws were followed by the vice laws 1911, which sought to address prostitution, abortion, pornography and homosexuality. In the aftermath of newly introduced children’s and vice laws, the police departments in some of the larger cities established vice and children’s departments. It was in the context of these departments that the first female officers were hired in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s. Female officers were thought to particularly suitable to speaking to children and women about sensitive subjects, including prostitution and sexual abuse.

The aftermath of the second world war, the Dutch government invested in developing the welfare state. This involved a re-centring of the family unit and a reiteration of the importance of the man’s role as the breadwinner and the woman’s role as mother and housewife. Still, in this generally conservative social and political climate, a few important milestones for women’s emancipation were achieved. In the latter half of that decade, women became legally competent and a rule mandating that women were fired from civil service jobs upon marriage was abandoned. That is not to say, however, that it immediately became socially accepted for women to continue working after marriage and especially after having children.

As elsewhere, the 1960s and 1970s were marked by the efforts of second wave feminist and LGBT emancipatory movement. Women’s participation in the workforce slowly increased from the 1960s, and the discriminatory article 248bis was abolished in 1971. By the 1980s, however, only 3 in 10 women had a job of 12 hours a week or more. In 17% of families with underaged children both partners worked. This increased to 43% by 1994. The marital exception in the rape law was removed in 1991. Same-sex marriage was legalised in 2001, making the Netherlands the first country to do so

From the late 19th Dutch society was characterised by pillarisation along religious and political lines. That is to say; Protestants, Catholics, socialists and liberals lived, to a significant extent, separate and parallel lives; served by different political parties, schools, press and professional organisations. In the context of the policing and legal system this had an effect on, for example, police unions and resocialisation of convicts. During much of the 20th century, the resocialisation and supervision of convicts after, or in place of, a completed prison sentence, was the purview of private probation services. Different organisations served convicts belonging to the different pillars.

De-pillarisation took place in the late 1960s and 1970s.

In the Dutch criminal code [Wetboek van Strafrecht] crimes against morality are covered in articles 239 to 254 in book II, title XIV. Articles 242 to 249 deal with what might be termed sexual violence. They include separate articles for rape (242), sexual assault of an adult without penetration (246), sexual intercourse with underaged girls (244 and 245), indecency [ontucht] with a child under the age of sixteen (247) and indecency with a minor under one’s education or care (249). Until 1971, the discriminatory article 248bis criminalised homosexual acts with a person under the age of 21, effectively setting the age of consent for same-sex relations 5 years higher than for heterosexual relations.

Article 242 on rape [verkrachting] reads as follows:

He who, by violence or threat of violence, forces a woman to have extramarital sexual intercourse with him, will, being guilty of rape, be punished with a prison sentence of no more than twelve years. [Hij die door geweld of bedreiging met geweld een vrouw dwingt met hem buiten echt vleselijke gemeenschap te hebben, wordt als schuldig aan verkrachting gestraft met gevangenisstraf van ten hoogste twaalf jaren.]

The law existed in this formulation from 1886 to 1984, when the possibility of imposing a fine was introduced. In 1991, the law was changed once more, removing the marital rape exception, making the law gender neutral, broadening the conditions under which a person could be said to have been forced and replacing “sexual intercourse” with “sexual penetration.” Several of the aforementioned articles underwent similar changes.

Title XIX of book II of the criminal code deals with “crimes against life.” This includes manslaughter (287), aggravated manslaughter (288), murder (249) and infanticide (290 and 291). Manslaughter [doodslag] is understood as intentional homicide, while murder [moord] is premeditated intentional homicide. The infanticide statutes mirror this distinction: article 290 deals with kinderdoodslag and article 291 with kindermoord. Both infanticide articles apply only to mothers who kill their children during or shortly after birth, out of fear for the discovery of their deliveries. Cases concerning individuals apart from the mother involved in the killing of babies and cases where the fear of discovery plays no role are charged as murder or manslaughter.

In the period 1911-1965, with the exception of World War II, the number of homicide victims was approximately 0,4 per 100.000 inhabitants. Between 1965 and 1990, partially due to the introduction of drugs in the Netherlands, there was a significant gradual increase in the number of homicide victims. By 1990, the number was at 1,2 per 100.000 inhabitants, after which the rate remained stable.

Between 1930-1960, based on documentation concerning the court in Utrecht, the most commonly tried sexual offence was indecency with children (247), accounting for approximately 64% of all sexual violence cases. The second most commonly tried type of case was indecency with a minor under ones care or education (249), which accounted for a further 15% of all sexual violence cases.

In that same period, psychiatrists were involved in approximately 60% of all cases of indecency with a child (247). Psychiatric expertise was more commonly called on in cases of this type when they concerned same-sex offences (69%) than in cases involving heterosexual offences (47%). Psychiatrists concluded that suspects examined could not, or could only partially, be held responsible in approximately 77% of these cases.

Based on documentation about the Utrecht prosecutors’ office, approximately 44% of cases reported to the prosecutor were dismissed before making it to trial. The chance of a dismissal was higher (53%) if the victim was an adult, versus when the victim was a child or minor (42%).

Throughout the 20th century, appointing expert witnesses in Dutch criminal cases has fallen within the purview of judges in the Netherlands. Both the prosecutor and the defence were able to make requests for a specific expert to be appointed, but such a request must be granted by either the investigative judge or the trial judge(s). Indeed, expert witnesses were expected to contribute to the court’s fact finding mission and do not serve as witness for either the prosecution or the defence.

Judges had free choice of which experts to appoint. In practice, however, courts typically relied on a small number of trusted experts who were appointed again and again. This situation was amplified in the late 1940s and 1950s, with the establishment of a number of specialised institutes.

In cases of suspicious death an autopsy was required and, after 1920, preferentially performed by the country’s main forensic pathologists (between 1920 and World War II typically J.P.L. Hulst and after World War II until 1984 Jan Zeldenrust). Due to the relatively low number of homicides, these two men (and, in the case of Zeldenrust, his assistants) were able to cover most of such cases, but before 1920 and occasionally after, other pathologists were also involved.

Investigation of the suspect’s mental state by a psychiatrist or (later) psychologist was a common feature of many criminal investigations. Typically, the psychiatric report built on a report drawn up by a probation official; the two reports together contributed not only to the question of accountability, but offered guidance to the judge with regard to the appropriateness of certain post-sentencing measures for that specific offender (i.e. imprisonment, probation, therapeutic measures).

Experts put their findings in written reports. If necessary, they could be required to explain or expand upon their report in court, though this was not especially common. In general, Dutch trials rely rather heavily on written documentation.

Throughout the nineteenth century, complaints about the quality of forensic medicine were omnipresent in the Netherlands. Neither education, nor legal provisions, nor amenities were considered sufficient to enable doctors to develop their skills and perform their tasks. Neither a 1818 regulation mandating the appointment of “sworn forensic district medicinae doctores and surgeons” nor the 1865 medical laws were felt to fix the situation. Doctors also complained that, to perform forensic duties, they were forced to abandon their own practice, losing valuable time and resources in the process. Only in 1920 a specialised forensic doctor was appointed.

The period 1870-1890 saw a growing influence of forensic psychiatry: the rise of criminal anthropology and the Nieuwe Richting [New Direction] in criminal law — a movement which emphasised not retribution against, but protection from criminal actors — put the accused’s personality centre-stage. Psychiatrists were increasingly invited into the courtroom to contribute their professional opinions about the mental state of suspects and victims.[3] Still, it wasn’t until the interbellum that legislation was enacted that underpinned the role of psychiatry in the legal system.

Criminalistics, meanwhile, began coming into its own at the turn of the twentieth century, in the context of police modernisation efforts. Local police services and their newly established unions led the charge to learn about and incorporate new techniques, such as photography, bertillonage and fingerprinting. A small group of private experts, running private laboratories, occasionally assisted police. The most famous of them, Co van Ledden Hulsebosch, established a school for criminalistics in 1914 and formally became a scientific adviser to the Amsterdam police – he was the only expert able to devote himself fulltime to criminalistics.

In the early part of the 20th century and during the interbellum years, calls for the establishment of specialised institutes for forensic medicine (esp. pathology), forensic psychiatry and criminalistics were heard. Funding-problems and war got in the way, however, and it was not until 1945 that the long-held plans came to fruition. With the establishment of the Gerechtelijk Laboratorium [Forensic Laboratory] in 1946, the Psychiatrische Observatie Kliniek [Psychiatric Observation Clinic] in 1949, and the Gerechtelijk Geneeskundig Laboratorium [Forensic Medical Laboratory] in 1951, a new generation of experts, contrary to their predecessors, would coalesce around these central institutes.

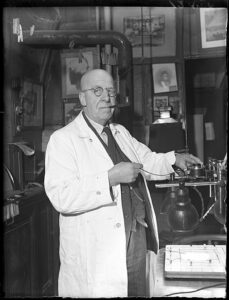

Undoubtedly the most famous of the police experts operating in the Netherlands before World War II was

Christiaan Jacobus van Ledden Hulsebosch

(1877-1952.) He got his apothecary degree from Amsterdam University in 1902, after which he pursued criminological chemistry and physics in Launsanne, Berlin, Dresden and Vienna.

He took over his father’s apothecary in 1910, after which he established a private laboratory — “equipped with the most modern machinery” — that became a central hub for criminalistics research. Police called on his assistance often and in 1916 he was officially made a scientific adviser for the Amsterdam police.

Van Ledden Hulsebosch enjoyed international renown for his academic contributions to scientific policing and in 1929 he became one of the founders and first president of the Académie Internationale de Criminalistique.

Willem Frederik Hesselink (1878-1973) received a degree in chemistry from Leiden University in 1901 and continued his studies in Munich, where he gained his cum laude doctorate in 1904. For a short while he worked in the laboratory of Dr. Popp in Frankfurt, where he was introduced to criminalistics. Upon his return to the Netherlands he established his Laboratorium voor Chemische en Microskopische Onderzoeking [Laboratory for Chemical and Microscopical Investigation] and made himself available to police and judiciary as an expert. He testified in a variety of court cases and, in 1910, Hesselink was appointed director of the Keuringsdienst van Waren [a quality and health inspection service.] He was a well-known expert in the controversial field of graphology and is remembered for his contributions to the field of blood stain analysis. Curiously, his biggest claim to fame may be that he was a star player on the Dutch national football team and one of the founders of the Arnhem-based football club Vitesse.

Joseph Emile Hubert van Waegeningh (1870-1944) — military man, apothecary and photographer of some renown (even photographing prince Hendrik, husband to queen Wilhelmina, at one point) — cut his teeth on criminalistics when asked to photograph the crime scene in the murder case 11-year old Marietje Kessels. From that point forward, Van Waegeningh was frequently called upon to use his photography skills in the service of justice. Apart from crime scene photography, he developed skills in toxicology (a logical step from being an apothecary, perhaps), graphology and ballistics among others. In 1913, he established the Bureau voor Chemisch-Mikroskopische Onderzoekingen [Bureau of Chemical-Microscopic Investigations] in Breda, where, aside from judicial investigations, he, like Hesselink, performed investigations into the quality of products meant for consumption.

Amsterdam police inspector Willem Schreuder played an important role in the professionalisation of police work, by publishing a number of books on the subject of scientific policing.[1] His 1930 handbook, which, like Hesselink’s, was also called Eerste optreden op de plaats eens misdrijfs, described several do’s and don’ts at a crime scene, laid out what to expect at different types of crime scenes and explained the use of various forensic techniques; Schreuder covered crime scene photography, fingerprinting, footprint-, bloodsplatter- and handwriting analysis, ballistics and others.

In the period before the Second World War, the most prominent forensic doctor in the country was Jean Pierre Louis Hulst (1875-1967). Having trained under the psychiatrist Binswanger and the psychiatrist, prosector and criminal anthropologist Jelgersma, Hulst worked as an assistant-prosector in the Boerhaave Laboratorium in Leiden — where he developed his skills in forensic medicine — until 1920. In that year he formally became a forensic doctor, entirely dedicated to serving the judiciary. One year earlier, his skills in this field had already been acknowledged when he was given a lectorship in forensic medicine and criminality at the Tropisch Instituut in Leiden and Rotterdam. Hulst travelled widely to perform forensic autopsies and to testify in courts throughout the country. From his own and his colleagues’ publications it would appear that Hulst was almost exclusively occupied with performing autopsies — though at least one historian has discussed the doctor’s involvement in a rape case.

Dr. Anna Johanna Steenhauer (1894-1965) worked alongside internationally renowned professor Leopold van Itallie (1866-1952) at the pharmaceutical- toxicological laboratory at Leiden University. Both Steenhauer and van Itallie acted as expert witnesses in numerous court cases. In 1933 she was a co-founder of the Leidsch Criminologisch Instituut. In 1949 she accepted a professorship of toxicology and forensic chemistry in 1949, dedicating her inaugural lecture to Hedendaagse vergiftigingen en hare opsporing [Present-day poisonings and their detection].

Dr. Anna Johanna Steenhauer (1894-1965) worked alongside internationally renowned professor Leopold van Itallie (1866-1952) at the pharmaceutical- toxicological laboratory at Leiden University. Both Steenhauer and van Itallie acted as expert witnesses in numerous court cases. In 1933 she was a co-founder of the Leidsch Criminologisch Instituut. In 1949 she accepted a professorship of toxicology and forensic chemistry in 1949, dedicating her inaugural lecture to Hedendaagse vergiftigingen en hare opsporing [Present-day poisonings and their detection].

Chemist dr. Wiebo Froentjes (1909-2006) made his start in the field of criminalistics as a court expert in Groningen. He became the first director of the Gerechtelijk Laboratorium [Forensic Laboratory] after its establishment in 1946. In 1953 a chair of criminalistics was established at Leiden University by the Prof. Mr. A.E.J. Moddermansstichting, a foundation with the explicit aim of ‘studying criminal law and its auxiliary sciences.’ Froentjes held this chair from 1953 to 1980, and he was succeeded by Prof. dr. E.R. Groeneveld (1934), who also took over as director of the Gerechtelijk Laboratorium.

Dr. Jan Zeldenrust (1907-1990) trained as a pathologist under Hulst. He went on to become the director of the the Gerechtelijk Geneeskundig Laboratorium (later the Laboratorium voor Gerechtelijke Pathologie) when that institute was established. Zeldenrust was, until his retirement in 1984, the only full-time forensic pathologist in the country. In his early years he worked alone, performing some 300 autopsies per year, after which he got the help of a part-time assistant, dr. M. Voortman, who would eventually be his successor. A second assistant, H.A.M. Janssen also joined the Gerechtelijk Geneeskundig Laboratorium. By 1984, the team performed some 500 autopsies per year.

Dr Pieter Aart Hendrik Baan (1912-1975) was a forensic psychiatrist. He became the first director of the Psychiatric Observation Clinic [Psychiatrische Observatie Kliniek, POK] when it was established in 1949. In 1978 that clinic was renamed in honour of its founder.