Atlas of Forensic Culture – England

By Pauline Dirven

On 7, 8 and 9 January 1932, five expert witnesses gave testimony in the case of Peter Queen. His girlfriend, Christiana Gall was found dead in their bed with a rope around her neck. The question at stake was if Peter had strangled her or she had taken her own life. The forensic experts could not agree with each other. The contradictory evidence they gave, led a newspaper to conclude that the experts had left the public with the impression that the medical evidence meant nothing. Moreover, it seemed that this forensic evidence only gained meaning in relation to the evidence concerning the characters and behaviour of the victim and the accused. The killing of Christina Gall is a case that illustrates the impact of the binary nature of the English and Scottish adversarial jury system on the role expert evidence played in the courtroom and the media.

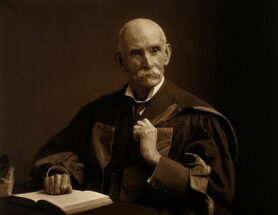

Experts called by the Crown included the emergency surgeon who first viewed the body and two pathologists, including professor John Glaister Jr.

John Glaister. Photograph by T. & R. Annan & Sons.

Iconographic Collections, Wellcome Collection. CCBY4.0

They testified that they could not conceive that the injuries were self-inflicted. The defence relied on the testimony of the popular pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury and Professor Sydney Smith. Contrary to their colleagues, they argued that the evidence indicated self-destruction. All the experts agreed that the cause of death was asphyxia due to strangulation. The victim’s internal organs and the mark around her neck provided them with the evidence to support this. The question they debated was how strangulation had taken place.

According to the experts called by the Crown, the mark on the victim’s neck indicated that fairly considerable force was used. They interpreted this as a sign that death would have followed rapidly. Moreover, the mark on and fracture of the cricoid – the ring of cartilage that surrounds the windpipe – indicated that the ligature would have produced unconsciousness when pulled tight. This in combination with the circumstances in which they had found the body excluded the possibility of suicide according to them. The left arm of the victim was stretched out to the side and the right arm of the victim had lain underneath the bedclothes, which were tucked over her breast while the ends of the rope were on her chest well away from the arms. According to them, it was inconceivable that the arm of the victim would end up underneath the bedclothes after she had rapidly lost consciousness.

The experts acting on behalf of the defence also referred to the circumstances in which the body was found to interpret how death had occurred, however, they argued that these ruled out suicide. Contrary to their colleagues, Spilsbury and Smith argued that the degree of force used in the strangulation was not very considerable, as there was no injury to the deeper part of the skin, the muscles of the neck and the thyroid gland. Moreover, they pointed out that the rope was only tied in a half-knot. All of this indicated suicide as their experience told them that a strangler normally pulls the ligature very tight, keeps the pressure up and does not want to run the risk of letting the knot slip by only tying it half. To this, they added that the undisturbed state of the room, the tidiness of the victim’s clothes and the fact that her dentures were in place indicated no struggle.

Because of the contradictory nature of the expert evidence, the eventual outcome of the case rested primarily on the way these experts’ reconstructions of the events related to the evidence concerning the characters and behaviour of the defendant and the victim. The case of Crown depended on the suggestion that no signs of struggle were found on the crime scene because Christiana Gall was asleep and intoxicated by alcohol at the time of the crime and could not resist. Even though the pathologists had not detected a smell of alcohol in her stomach and omitted to carry-out chemical tests on her stomach contents or blood to detect alcohol, the Crown referred to Christiana’s character to argue that she had been intoxicated. The Crown called various witnesses to portray Chrissie, as she was called, as an unhappy woman driven to drink. The prosecution emphasized Chrissie started drinking when her mother died and that this habit had grown worse after her father sold her parental home and she decided to live with her lover. She turned to alcohol out of the shame she felt for living with Peter outside of wedlock and the stress it gave her to lie about it to her family. It grieved her that she could not marry Peter who was already married but had been separated from his wife after two years of marriage when she was incarnated in an asylum. Chrissie’s unhappiness resulted in frequent intoxication, two suicide attempts and multiple threats about taking her own life.

The case of the Crown rested on the argument that Chrissie resented her life that did not conform to cultural concepts of female respectability and marriage. Her behaviour was presented as a motive for murder. The judge, in his summing up, pointed to its significance and proposed to the jury that they should consider whether it was conceivable that ‘because of the embarrassment created by the illicit relationship between the two that a breaking point was reached, and that accused was so completely disgusted with her conduct and so sick of the embarrassment that he decided to take her life’. The case hinged on the question of whether Chrissie’s non-conformative behaviour, which was labelled ‘provoking’, ‘embarrassing’ and even ‘disgusting’, and the couples’ lack of conformation to the marital norm, could serve as a motive for murder.

The jury was convinced that it could and returned the verdict of guilty. However, they added a unanimous recommendation for mercy. The cry for mercy was picked up by the newspapers and the general public who campaigned for the reprieve of Peter’s death sentence. The papers emphasized that the experts were unable to agree. Moreover, they stated that many people felt sympathy for Peter who appeared to have always cared for his troubled girlfriend and never showed any desire to ‘get rid of her’. The journalists had a part to play in inciting this sympathy through their description of the emotional behaviour Peter displayed in the witness box. They emphasized that Peter was very distressed, on occasions almost fainted and that his voice sunk to a whisper when he recounted how he discover that his lover was dead.

A similar appeal to Peter’s emotional and caring performance was made by one of the defence experts Smith, whose evidence had not convinced the jury. In his 1959 autobiography, Mostly Murder, he aims to strengthen his expert opinion by remarking that there was ‘not time in their history when anybody had noticed the slightest sign in him of irritation or impatience towards her, or of anything but loving care and attention. Could his hand have tied the cord around her neck and held it tight for some minutes while he watched her slowly die? I cannot believe that possible’. In addition to the medical findings, Smith presented Peter’s emotional display as support for his suicide theory. Eventually, Peter’s performance of love and care saved his life because his death sentence was changed into penal servitude for life which resulted in an early release.

1922

Infanticide Act

This measure abolished the death penalty for women who had murdered their new born babies, at a time when their minds were disturbed as the result of giving birth. Instead it ‘created a new homicide offense of infanticide, akin to manslaughter in terms of its gravity and punishment (which was a maximum of penal servitude for life).

1924

Publication of 'Forensic Medicine: a Textbook for Students and Practitioners'

Book written by Sydney Smith, Forensic Medicine: a Textbook for Students and Practitioners. Professor Sir Sydney Smith was a renowned forensic scientist and pathologist. He was an authority in the field of ballistics and firearms in forensic medicine, and held several prominent positions at the University of Edinburgh.

1927

Publication of the last story of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle

The last story of Sherlock Holmes written by Arthurt Conan Doyle was first published in American Liberty Magazine in 1927, titled ‘The adventures of Shoscombe Old Place’. It was later published as part of The Case-book of Sherlock Holmes.

1930

Meeting between The Medico-Legal Society and The West London Medico-Chirurgical Society on ‘the doctor in the law courts’.

1934

The Ruxton Case

The Ruxton Case (also known as the “Jigsaw Murders”) was a very highly publicized case in 1930s. Buck Ruxton, a British physician was convicted for the murder of his wife and his housemaid. The murders became well known due to Ruxton’s efforts to make the bodies unrecognizable by mutilating their bodies and disposing of them, requiring extensive work to reassemble and identify them. Novel forensic techniques were used to do so, including forensic anthropological and entomological techniques.

1935

Establishment of the Metropolitan Police Forensic Laboratory

1938

Infanticide Act

What would ordinarily be murder is reduced to manslaughter if, at the time of the killing, ‘the balance of her mind was disturbed by reason of her not having fully recovered from the effect of giving birth to the child or by reason of the effect of lactation’.

1947

Death of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1877-1947)

Sir Bernard Spilsbury was a well-known British pathologist, known for his court room appearances. For more information, see below under ‘Experts of Note’

1948

Death of Charles Ainsworth Mitchell (1867-1948)

Charles Ainsworth Mitchell was a British Chemist and scholar of the microscopic and chemical analysis of handwriting.

1955

Publication of 'The Essentials of Forensic Medicine' by C.J. Polson

1956

Sexual Offences Act

The Sexual Offences Act states ‘person shall not be convicted of an offence under this section on the evidence of one witness only, unless the witness is corroborated in some material particular by evidence implicating the accused’. Hence great importance is attached to the medical and scientific evidence, which frequently supplies the only corroboration.’

1957

Homicide Act

This reform of the English law included a number of changes, including the introduction of the defense of diminished responsibility.

1960

Publication of 'Forensic Medicine: Observation and Interpretation'

Forensic Medicine: Observation and Interpretation was written by Arthur Keith Mant, a British forensic pathologist who headed the Special Medical Section of the British Army’s War Crimes Group.

1967

Abortion Act

The 1967 Abortion Act was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which legalized abortions on certain grounds when provided by registered practitioners.

1969

Death of Sydney Smith (1883-1969)

1970

Rise of the female protagonist in detective fiction

1976

Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act

Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act: rape is defined as ‘unlawful sexual intercourse by a man with a woman who, at the time of intercourse, does not consent, or is reckless as to whether she consents’.

Death of Agatha Christie (1890-1876)

1979

Battered Women Syndrome coined by Lenore E. Walker

The term “Battered Women Syndrome” is coined by Lenore E. Walker. She described it as consisting “of the pattern of the signs and symptoms that have been found to occur after a woman has been physically, sexually, and/or psychologically abused in an intimate relationship, when the partner (usually, but not always a man) exerted power and control over the woman to coerce her into doing whatever he wanted, without regard for her right or feelings.”

1984

Invention of DNA-profiling by Sir Alec Jeffreys

On Monday 10 September 1984 at 09:05 in the morning, Alec Jeffreys had a moment of revelation in his lab at the University of Leicester. Looking at the X- ray of a DNA experiment, he realised that it showed both similarities and differences in his technician and family’s DNA. In that moment genetic fingerprinting was born, and in the 25 years since then the technique has been of enormous help in police investigations.

1988

The Pitchfork Case

The so-called Pitchfork Case was the first murder case where a conviction was based on DNA evidence.

1991

New perspectives on the notion of marital rape

House of Lords rules in appeals case of attempted marital rape: ‘Nowadays it cannot seriously be maintained that by marriage a wife submits herself irrevocably to sexual intercourse in all circumstances.”. Took into 2003 for marital rape to be explicitly laid out in the sexual offence act.

1994

Sexual Offences Act

Sexual Offences Act now also made non-consensual buggery by a man of a man or woman an act of rape. (first time forced sex of a man by a man is defined as rape)

1995

UK national DNA Database

Below is a short discussion of the general characteristics of England and the context in which its forensic culture developed.

England, as part of Great Britain, had, and continues to have a parliamentary democracy. Until the 1970s the country was a ‘welfare state’ which was sustained by principles of ‘economic growth, declining inequalities and increasing social mobility’. Its crime policy focused on the rehabilitation of offenders and the development of favourable social conditions that were believed to prevent crime. However, in the 1970s and predominantly after the formation of the Thatcher government, Great Britain became a ‘security state’ that focused on crime as a risk that needed to be managed by the implementation of tougher sentences.

In the early and mid-twentieth century, England was predominantly protestant, as the majority of the population belonged to the Church of England. Later in the twentieth century, England became predominantly secular.

Modern Adversarial System

In the middle ages and early modern period, trials were informal, local confrontations between the accused, the injured and the community. The jurors were chosen for their direct and personal knowledge of the case and acted as witnesses, investigators and often also as experts. This communal practice of criminal law diminished from the eighteenth century onwards. The modern British adversarial legal system developed that became typified by its uniform application of the law, the emergence of the defence lawyer who came to speak for the defendant, the anonymization of the jury and the development of rules of evidence.

In the twentieth century, this modern adversarial legal system was in place. In it, criminal law was primarily founded on common law. The trial was no longer a communal drama, but an anonymised practice in which the judge was required to oversee that the law was applied in a uniform and impersonal manner. Moreover, this modern legal system was party based; it required the public or state prosecutor to bring the accusation against the defendant, who was usually represented by a defence counsel. Defendants did not have to prove their innocence. Instead, the prosecuting counsel needed to prove their case ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ before a magistrate, judge, or jury. In this new system, experts obtained a new role. They were no longer members of the jury or court experts, but instead party witnesses who testified to medical and scientific evidence related to the case at hand.

The Criminal Courts

In the English system, between 1920-2000, a defendant could go through different trajectories of court appearances before a verdict was reached. Throughout the whole century, the Coroner’s court functioned as an inquest in cases of death. The task of this court was to decide, by jury verdict, whether the deceased has come to their death by murder or manslaughter. Other criminal cases came before the Magistrates’ court (formerly known as police courts in London or petty sessions elsewhere in the country) in the first instance. When it concerned minor cases, this court could pass a sentence, but in more serious charges this court functioned as a preliminary examination to decide whether the case should be sent to a higher court for trial. If the Coroner or Magistrate court established that a serious criminal case could be made, the case was referred to the Assize court where the defendant was tried before a jury. If the defendant was found guilty, the convicted could appeal in the Court of Criminal Appeal.

In addition to this trajectory, indictments not punishable with penal servitude for life could also be tried by the Courts of Quarter-Sessions. The Quarter-Sessions were held four times a year in each county and in practice dealt with lesser felonies and misdemeanours.

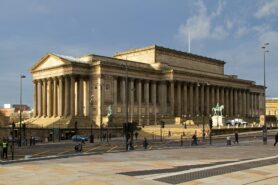

In 1956 two additional courts were set up: the Crown courts at Liverpool and Manchester which took over the function of the Assize court and Quarter sessions. The Courts Act of 1971 replaced all the English Assize courts and Quarter Sessions with the Crown Court. In this new court system, cases concerning serious offences in Greater London were referred to the Central Criminal Court.

Gender of forensic experts

During the first decades of the twentieth century the women’s movement created more opportunities for middle-class women to enter formal education, stimulated them to grow to be more economically independent and campaigned for political reform. While women’s labour force participation stagnated until the 1930s (except for a temporary increase during the First World War), the early twentieth century did see the entrance of women in occupations formerly exclusively accessible to men. This was also true in the criminal justice system, in which the first policewomen were employed in 1919 and the first female police surgeon, Dr Neillie Beatrice Wells, was appointed in 1927.

It was only between 1969 and 1973, when a national increase in women’s workforce participation occurred and the male-breadwinner ideal disappeared, that women were integrated into the police corpse on the same terms as their male colleagues. For most of the twentieth century, women’s participation in the realm of forensics was approved because of the idea that they were specialists in crimes committed by or against women and children. The tasks of policewomen were often associated with caring activities for women and children and Dr Wells claimed her place in the forensic realm by emphasizing that a female doctor was required to examine victims of sexual offences.

Until the end of the century, medical examiners and women’s organisations continued to spread Wells’ call for the appointment of more female medical examiners for sexual offence cases. However, while female rape victims often preferred to be seen by a woman doctor, they were in short supply until the end of the century. Female experts were often unavailable on short notice. And even if they were, their involvement did not guarantee a sympathetic attitude towards the victim, nor the abolishment of rape myths in their reports and testimony.

In other realms of forensic expertise, women had a difficult time obtaining positions. The middle and second half of the twentieth century saw the involvement of more women in forensic examinations as secretaries, scientists and pathologists. However, it took a while for them to be accepted as experts on crime because the forensic laboratory and mortuaries were not considered ‘suitable places’ for women. Until the end of the century, stereotypical ideas about women’s incapacity to deal with the ‘gruesome’ realities of the mortuary and their tendency to faint at the sight of something scary continued to exist. Still, from the 1980s onwards, women became more visible in the forensic realm as pathologists, scientists and forensic secretaries who wrote autobiographies and appeared in the media.

Gender norms and sentencing

Gender impacted courtroom proceedings, as ideas about gendered normative behaviour and the gendered role people played in society, informed the jury, lawyer and judges in their decision-making process. If a defendant or complainant displayed behaviour conformed to gender norms and prevalent ideas about male and female sexuality this could positively influence the outcome of the trial. What this looked like, was highly gendered. For example, while both men and women on trial for child murder were expected to display sorrow, women needed to show that they were consumed with grief, while men needed to perform a more restrained form of sadness.

Such gendered ideas about respectability explain the high numbers of acquittal or reprieve amongst murderesses of their children and abusive spouses in England and Ireland. For example, in the first half of the twentieth century, women were more likely to be sent to a medical institution than receive the death penalty because people believed that women were more frail than men and therefore likely to suffer from mental illness. In general, sentencing practices depended on the jurors’ and judiciary’s ideas about gendered behaviour and gender structures in British society.

Gendered criminal behaviour

The influence of gender ideology on the justice system is not only apparent in sentencing practices. It also becomes visible in debates on the gendered ‘nature’ of crime. In the courtroom, the media, and medical and scientific research ideas on gender-specific criminal behaviour circulated. This concerned both ideas about the kind of offences that men or women would commit and expectations on how both parties would behave in an act of violence. Such gendered ideas about crime impacted forensic culture as forensic experts consciously and unconsciously applied them to the cases they examined. For example, the idea that ‘women make use of the less violent and cleaner forms of suicide’ made a Home Office Pathologist conclude in 1977 that therefore ‘a good rule of thumb is that a shot woman has been murdered until proved otherwise’.

The most prominent example of the impact of such gendered notions about criminal behaviour on forensic examinations is the influence of rape myths, i.e. ideas about what a ‘real rape’ should look like. In the twentieth century, these included the assumption that women would fight their assailant, that women and children made false accusations of rape, that men could not ‘turn off’ their arousal in the heat of the moment, that the moral character of a woman determined her credibility, and that rape was most frequently committed against virgins. Informed by these notions of what rape entailed, police surgeons and other forensic doctors modelled their examination practices along the lines of gender prejudices. They did so by searching for defence wounds, commenting on the victim’s dress, or noting down whether they believed that the victim’s weight and build would have allowed her to ‘overcome’ and fight off the rapist. In these ways, cultural ideas about femininity, masculinity and sexuality shaped forensic knowledge-making practices.

Newspapers

For much of the researched period, especially between 1918 and 1978, newspapers were an integral part of British popular culture as the vast majority read at least one national paper. This media platform impacted forensic culture as the press’ coverage of the judicial system had a significant influence on public perceptions of crime, and, by extension, of the ‘state of society’’.

Court and crime reporting formed a significant aspect of journalism in twentieth-century Britain. It catered to the newly developed fascination with human interest stories in the 1920s. At this time, the emergence of photojournalism had personalized and sensationalized articles. Crime formed a suitable topic for this new journalistic trend, as it provided readers with cheap, regular and shocking human interest stories. Journalists reported on the personal and family background of infamous criminals and victims of crime and, especially in the 1920s-1940s, provided their reader audience with stories on forensic experts who became public figures of interest.

In general, in the twentieth century, the genre of court reporting had become a passive genre as they were often literal transcriptions of what was said in the courtroom and were only rarely accompanied by editorial comments, analysis or criticism. Though there was some space for reflection in the headlines the journalists chose. In general, crimes were represented as individual problems and not as signifiers of a wider social issue.

This trend was critiqued throughout the twentieth century as the popular press was accused of letting its financial interest in the cheap, glamorized and sensational crime reports, often filled with gruesome details, overshadow its social responsibilities. Moreover, it impacted the administration of justice. First, because jurors and civil servants were confronted with articles on the cases they were involved in. And second, as feminists pointed out in the 1970s, because the contemporary increase of articles on rape cases and their explicit content that included personal details of the victims discouraged women from reporting the crime to the police.

Class was one of the most important categories of social identity in twentieth-century Britain. During the twentieth century, the social stratification of British society changed. The aristocracy’s political power diminished and non-property owning men (1918), property-owning women (1918) and non-property owning women (1928) received the right to vote and in 1919 property-owning men and women and 1974 everyone registered on the parliamentary or local government list of voters could serve as jurors. Moreover, the standard of living of the working classes improved after the shared experience of the Second World War. The welfare state was implemented and the 1950s saw the development of publicly funded council housing, making the 1960s and 1970s a period of relative economic gain. In the Thatcher era that followed, working-class people increasingly became homeowners, but simultaneously, social inequality grew during these decades.

Despite the latter trend, the number of people occupying a working-class job diminished increasingly in the second half of the century. Many women left domestic service on the eve of the Second World War and technological advancements in the 1960s enabled former working-class employees to take up middle-class jobs in technology, science and management. Whereas between 1900 and 1940s, the country was a working-class nation, with around three-quarters of the population classified as working class, this number decreased from 60,6 per cent in 1961 to 49.6 per cent in 1981 to 38.4 per cent in 1991.

While these political and social changes limited inequality and more people started to occupy middle-class jobs, the class society did not disappear. In fact, in the 1980s, two-thirds of the British population still described themselves as working class, while in reality only less than half of the workforce occupied a working-class function. Despite political, occupational and social changes, a cultural experience of class continued to shape people’s identity and social relations. In twentieth-century Britain, class was more than an occupation. It was a cultural marker of difference that gained shape in social practices, social geography, bodily performances and communal experiences.

These cultural expressions of class influenced British forensic culture. It shaped knowledge-making processes because doctors, police officers and other experts were influenced by prejudices and stereotypical ideas about members of the different classes. This, for example, impacted rape examinations. Forensic handbooks show that authors instructed their readers that working-class women – who they believed they could easily recognize by demeanour, attitude and clothes – had poorer hygiene, were more accustomed to rough physical interactions and were more knowledgeable about sex than ‘fragile’ upper-class women. Moreover, class impacted which actors participated in the legal system. Not only because property qualifications formally determined who could serve on a jury, but also because, until 1998, barristers on behalf of the defendant could challenge potential jurors without giving a reason, which often turned out to be class related. As a cultural category of social identity, class shaped forensic culture in Britain.

Honour played some role in infanticide cases in England and Ireland during the twentieth century. Infanticidal mothers were assumed to have committed their crime in an attempt to avoid the dishonour of bearing an illegitimate child. In this way they responded to an important gendered norm; women only bear children when they are married. This could partly explain why society at large, and forensic actors in particular, responded to cases of infanticide with leniency. The seemingly ‘unfeminine’ act of murdering a child, an act that challenged the essence of motherhood, was considered to be a way to adhere – though in the most desperate way – to cultural-gender norms during the first half of the twentieth century.

Until 1976 rape was defined by common law as ‘when a man hath carnal knowledge of a woman by force and against her will’.

The Offences Against the Person Acts of 1861 specified that ‘whenever, upon the trial for any offence punishable under this Act, it may be necessary to prove carnal knowledge, it shall not be necessary to prove the actual emission of seed in order to constitute a carnal knowledge, but the carnal knowledge shall be deemed complete upon proof of penetration only’. It also specified different sentences for rape and sexual relations with underage girls. Under this act both ‘illicit carnal connection’ with a woman under the age of twenty-one ‘by false pretences, false representations or other fraudulent means’ and ‘unlawful and carnal knowledge’ of girls between ten and twelve years of age became misdemeanours. The ‘unlawful and carnal knowledge and abuse’ of girls under the age of ten years old became a felony.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 specified that rape was also committed when a man ‘induces a married woman to permit him to have connection with her by personating her husband’. In addition, it decided that connection with mentally deficient girls was a misdemeanour punishable with two years hard labour and it raised the age for sexual maturity by making unlawful carnal knowledge of girls under the age of thirteen a felony and of girls between thirteen and sixteen a misdemeanour.

The Sexual Offences Act of 1956 stated a ‘person shall not be convicted of an offence under this section on the evidence of one witness only unless the witness is corroborated in some material particular by evidence implicating the accused’. Hence great importance was attached to the medical and scientific evidence, which frequently supplied the only corroboration.

In 1976 the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act redefined rape as ‘unlawful sexual intercourse by a man with a woman who, at the time of intercourse, does not consent, or is reckless as to whether she consents’.

In 1991 the House of Lords ruled in a case of appeal of attempted marital rape that ‘nowadays it cannot seriously be maintained that by marriage a wife submits herself irrevocably to sexual intercourse in all circumstances.” However, it took until 2003 for marital rape to be explicitly laid out in the Sexual Offence Act.

In 1994 the Sexual Offences Act also made non-consensual buggery by a man of a man or woman an act of rape.

The Offences Against the Person Act of 1861 defined murder. It specifies that ‘it shall not be necessary to set forth the manner in which or the means by which the death of the deceased was caused, but it shall be sufficient in any indictment for murder to charge that the defendant did feloniously, willfully, and of his malice aforethought kill and murder the deceased’. Murders received the death sentence and, as part of their sentence, were buried ‘within the Precincts of the Prison’.

Manslaughter, in contrast, was the charge that ‘the defendant did feloniously kill and slay the deceased’. If convicted with manslaughter a person was sentenced to ‘penal servitude for life or for any term not less than three years, or to be imprisoned for any term not exceeding two years, with or without hard labour, or to pay such fine as the court shall award, in addition to or without any such other discretionary punishment as aforesaid’.

It was specified that ‘no punishment or forfeiture shall be incurred by any person who shall kill another by misfortune or in his own defence, or in any other manner without felony’.

In 1957 the Homicide Act restricted the use of the death penalty for murder. It abolished the doctrine of constructive malice (except in limited circumstances), which attributed that malice aforethought could be attributed to a defendant who killed during the commission of another felony. Also, it reformed the partial defence of provocation and introduced the partial defences of diminished responsibility and suicide pact.

The Murder Act of 1965 abolished the death penalty.

The Infanticide Act of 1922 abolished the death penalty for women who had murdered their newborn babies, at a time when their minds were disturbed as the result of giving birth. Instead it ‘created a new homicide offence of infanticide, akin to manslaughter in terms of its gravity and punishment (which was a maximum of penal servitude for life)’.

The Infanticide Act of 1938 specified that what would ordinarily be murder is reduced to manslaughter if, at the time of killing a child up to 12 months of age, ‘the balance of her mind was disturbed by reason of her not having fully recovered from the effect of giving birth to the child or by reason of the effect of lactation’.

In 1967 the Abortion Act legalised abortion on a wide number of grounds.

Drawing on the situation of the two preceding decades, in the early twentieth century England did not have a formal system for the employment of forensic experts. Instead, medical witnesses were chosen because of their proximity to the crime in question. Hence, the professional background of forensic experts could be quite diverse. While for rape cases this remained the case throughout the twentieth century, in homicide cases a preference for the employment of Home Office-approved pathologists increased from the 1940s onwards. Until the establishment of the Metropolitan Police Laboratory in 1935, and the formation of national laboratories for forensic science and ballistics in the successive years, the English policing and forensic research system were locally organized. Because of that, detective and laboratory facilities varied throughout the country. In general, it was the practice to employ independent experts – for example, university professors – or public analysts who could undertake a wide range of scientific and technical forensic analyses, as all-round experts.

After the professionalisation of forensic science in the 1930s, this gradually changed. During the second half of the twentieth-century specialist organisations and journals began to develop, such as the Association of Police Surgeons in 1951. Moreover, as forensic laboratories permanently started to employ a chemist, physicist and biologist, specialist teams slowly began to replace the all-round medico-legal expert. The institutionalisation of forensic science enabled the establishment of the UK national DNA database in 1995. It is important to note, however, that while forensic services of the prosecution became institutionalised, forensic experts for the defence did not. Defendants continued to depend on the services of individual experts and consultancies.

Forensic expert witnesses occupied a complex position in the modern English courtroom. As doctors and scientists, expert witnesses needed to be neutral and able to give an unbiased opinion on the case in the courtroom. However, in practice, they were called into court by either the prosecution or defence party. This meant that one of these parties employed or ‘hired’ the expert and listed them as their witnesses, leaving them to cross-examination by the opposing party. In this two-party system, it proved rather difficult for expert witnesses to appear trustworthy and create a sense of scientific objectivity, as the format of the trial made them appear as partial witnesses or ‘hired guns’. Throughout the twentieth century, forensic experts had to carefully construct their courtroom performances to contest this suggestion of partiality and convince their audience that they were trustworthy and objective experts.

While this notion of impartiality continued to impact the performance of forensic expertise throughout the twentieth century, the enactment of expertise did not remain stagnant. Changes in the forensic culture impacted the way expertise gained shape. Whereas the first half of the twentieth century was marked by the cultivation of trust in individual experts with good public reputations, after the 1930s, the faith in expertise gradually began to rely on the public’s confidence in scientific institutions and specialised academic disciplines. As a result, after the 1960s, experts were less easily accredited with authority solely based on their individual experience and instead received their status from their association with established institutions.

This reflected a larger trend in the public reputation of science in Britain. From the 1960s and 1970s onwards from a trust in virtuous persons to a trust in institutions and the protocols or systems of control and peer review they have in place. It was no longer an individual, and his or her personality, that enacted expertise, but their affiliation with institutions whose administrative policies, image and training programmers.

In the realm of forensic culture, this shift from trust in experienced individuals towards faith in institutions accelerated when news media started to critically report on mistakes that forensic scientists had made. Journalists developed a more critical outlook on forensic expertise, especially when the scandal caused by Home Office forensic scientist Dr Alan Clift came to light in the appeals case of R. v. Preece in 1981. Clift was suspended from his job in 1977 and during the 1980s, when various of his cases were re-examined, Dr Clift was presented as a ‘liar’, who lacked objectivity and purposely silenced certain aspects of the case he researched.

The exposure of such scandals and the eagerness of the media to report on such mistakes made the position of expert witnesses more vulnerable.

Sir Bernard Spilsbury was a Home Office forensic pathologist, trained in bacteriology, ‘morbid anatomy’ and histology. He was a famous forensic expert, who became well-known after his performance in the Crippen case (1910) and acquired a celebrity status because of his involvement in the Mahon case (also known as the Crumbles case of 1924). His success depended on his authoritative communication skills, aristocratic bearing, media presence, unshakable self-belief and ability to ‘look the part’. While he became the public face of forensic expertise, during and after his life, he received lots of criticism from his colleagues. He is often portrayed as a dogmatic figure, who preferred to work alone and did not welcome criticism. His colleagues claimed that even though on occasion, he wrongfully interpreted the forensic material, the jury would side with him because of his charismatic performances and celebrity status.

John Glaister Jr., was a professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Glasgow 1931-1962. He was a pathologist, serologist, and expert on hairs and fibres. He is best known for his work on the Ruxton case (1935). This case revolved around the identification of body parts found on a river bedding in Moffat. Together with his team of experts, Glaister succeeded in reconstructing the dismembered bodies, identifying them and linking them to a crime scene. He was able to win the trust of the court because of his impartial performance, display of teamwork with other forensic experts and good collaboration with the police.

John Glaister and James Couper Brash, Medico-Legal Aspects of the Ruxton Case (Edinburgh, 1937).

John Glaister, Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology(Edinburgh, 1942).

John Glaister and Sydney Smith, Recent Advances in Forensic Medicine (London, 1931).

Born in New Zealand, Sydney Smith had an international career. He served as a Medical Officer of Health in the New Zealand department of public health, and as an examiner of public health at the University of New Zealand. Between 1917-1927 he became the principal Medical-Legal Expert of the Egyptian Government Service and professor of forensic Medicine in Royal Schools of Medicine and Law, Cairo. Here he developed knowledge of firearms and ballistics. He wrote down the knowledge he obtained here in Forensic Medicine: a Handbook for Students and Practitioners (1925). In 1928 he came to Scotland as he was appointed professor of forensic medicine at the University of Glasgow. From 1931 until 1953 he served as the dean of the Faculty of Medicine and from 1954 to 1957 he was the Rector of the University of Edinburgh. Smith testified as an expert witness in many different cases, inter alia the Ruxton case (1935).

John Glaister and Sydney Smith, Recent Advances in Forensic Medicine (London, 1931).

Between 1928 and 1956 he edited four editions of Taylor’s Principles and Practice of Medical Jurisprudence.

Sydney Smith, Forensic Medicine: a Handbook for Students and Practitioners (London, 1925).

Sydney Smith, Mostly Murder (London, 1959).

Dr Nasta Wells was the first female police surgeon in the country. From 1927 until 1954 she worked as a police surgeon for the Manchester City police. As a member of the Medical Women Federation, she made a case for employing more women in the police force and argued that rape victims and children should be interviewed and examined by women. In 1958 and 1961 she published her observations in two detailed and critical articles in the British Medical Journal.

H.J. Walls was a forensic scientist who specialized in spectroscopy. He was the Director of the Metropolitan Police Laboratories from 1964-1968 and the president of the British Academy of Forensic Sciences in 1965. He wrote several handbooks about forensic science, including a book on drinking, drugs and driving.

H. J. Walls, Expert Witness: My Thirty Years in Forensic Science (London: Random House UK, 1972).

H.J. Walls, Drinking, Drugs and Driving (London, 1972).

H.J. Walls, Forensic Science: An Introduction to Scientific Crime Detection (London, 1974);

H.J. Walls, ‘The Forensic Science Service in Great Britain: A Short History’, Journal of the Forensic Science Society 16 (1976): 273–278.

Keith Simpson was a Home Office pathologist. He worked at Guy’s hospital and became the first professor of forensic medicine at London University in 1962. His services as a forensic expert were frequently requested and he was involved in the examination of notorious cases such as the Dobkin case and the Acid Bath murders. He is also known for bringing ‘battered baby syndrome’ to his colleagues’ attention.

Keith Simpson, Forensic Medicine (London, 1947).

Keith Simpson, A Doctor’s Guide to Court (London, 1967).

Keith Simpson, Forty Years of Murder: An Autobiography (London, 1980).